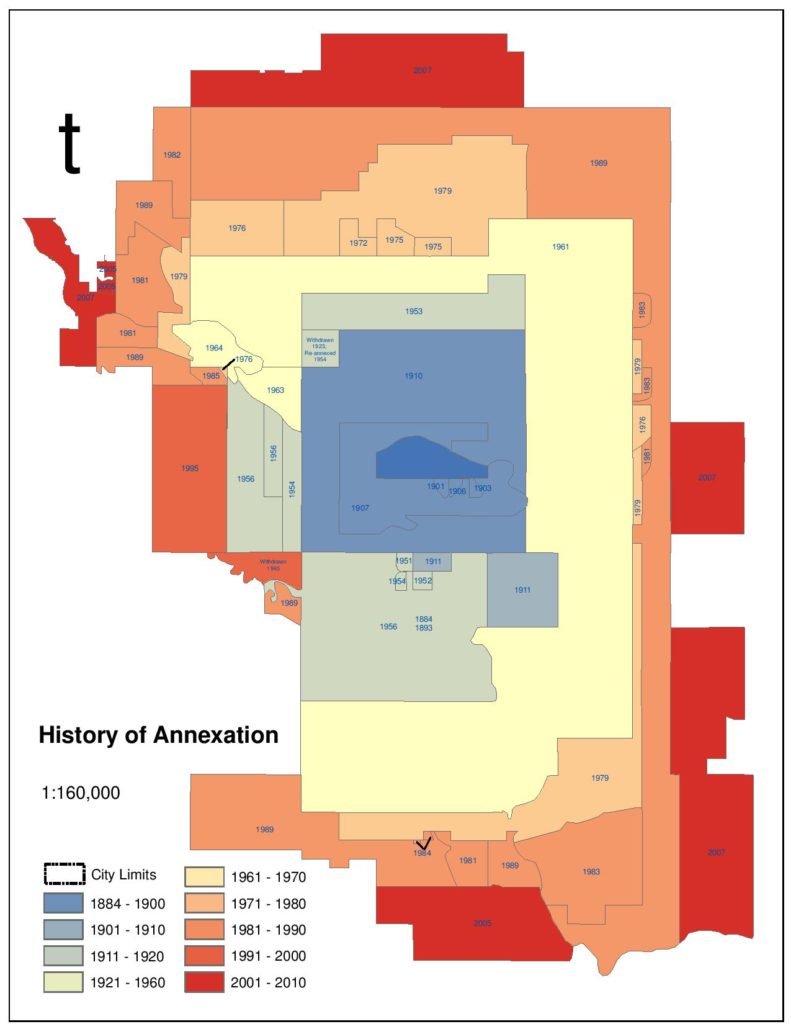

A decade ago, riding a bicycle in Toronto and Vancouver was, in some ways, a similar experience.

Two of Canada’s biggest cities, both had dense and walkable urban cores, but little in the way of bike-specific infrastructure, so riding through the city could be a harrowing experience. Both cities had thousands of cyclists who were keen on getting around safely, but there were also those who hated the idea of carving out space for cyclists, so fierce debates played out in the media and the local pubs over the idea of bike lanes.

Since then, the two cities went in different directions, and the results are palpable. At least, they are palpable if you were reading the local papers this weekend.

In Toronto’s Globe and Mail came yet another column lamenting the “Mad Max” scenarios between cars and drivers. After witnessing a frightening confrontation between a motorist and a cyclist, columnist Elizabeth Renzetti said summer in her city feels like “Death Race 2016.”

Over on the west coast, in contrast, the Vancouver Sun ran a long piece about the blossoming of businesses located along new(ish) separated bike lanes. The feature even quoted the leader of a downtown business group that was once hostile to bike lanes, who said there has been a “sea change” in attitudes toward cycling, as many business groups embrace the burgeoning scene and the spendy nature of those cyclists.

Bike routes good for business. #bikeyvr Chain reaction: Vancouver's burgeoning bike routes spin off new businesses https://t.co/hawP1MzwNX

— BikeMaps.org (@BikeMapsTeam) July 19, 2016

Neither piece is, of course, completely representative of their respective cities (Renzetti’s column is a tad dramatic, and the Sun’s piece is a tad optimistic), but they both are further signs of how much their respective cities have changed (or stagnated) for cyclists in the past decade.

First, Toronto: After an ambitious plan from city hall in the 1990s, Toronto went through a bikelash the likes of which few cities have experienced. After making some headway on the plan, late crack-smoking suburban populist Rob Ford was elected mayor in 2010, and he promptly went about dismantling what little progress the city had made for cyclists. With typically wrong-headed rhetoric, one of Ford’s first acts as mayor was to remove a recently installed bike lane. “The war on cars is over,” he famously said.

Six years later, a more forward thinking and reasonable regime is leading city hall, and the plans for making the city better for cycling are slowly being dusted off. In a city that is filled with so many bicycles only the willfully ignorant could deny their place with a straight face, those lost years are taking their toll. Progress is finally being made, which means the growing pains of its transportation infrastructure are being acutely felt, and the result is those portrayals of a bottled-up sense of hostility on city streets, confrontations, raging debates in the press, and those “Mad Max” analogies.

That scenario might sound familiar to Vancouverites. The city was within the throes of its own George Milleresque dustup over bikes just a couple of years ago, when plans to add a bike route sparked street protests, allegations of class warfare and general unpleasantness directed toward those on two wheels. The turnaround has been swift, with formerly hostile business owners making a complete turnaround, cyclists flocking to the new routes, and city planners trying to keep their I-told-you-so smirks in check.

That may seen a dramatic flip, but it’s not atypical. The controversies that dog bike-lane proposals seldom last long, often because well-planned and well-executed projects quickly prove their worth and then fall from the minds of reasonable people who were once opposed. That tends to leave those dug-in opponents looking like lonely cranks, like this guy.

https://twitter.com/PeterDormaar/status/626836873009238016

What worked in Vancouver, and in so many other cities, was the political courage to back a project that was well-conceived but contentious. Not every project will work, but sometimes giving them a try is worth the pain.

Toronto is a different city than Vancouver, with its own unique transportation and political problems, but you can’t help but wonder if those bike plans had been implemented all those years ago, Mad Max would exist only on Netflix.

.jpg?1398296708)