You’ve been there, even if you haven’t consciously been there: Riding your bike down a typical city street feeling squeezed from all sides, unable to see past the next intersection, worried about being doored and generally unwelcome on what should be public space.

Why do you feel that way? Because the street looks like this:

There’s nothing wrong, technically, with this street. These scenes are everywhere. But the reason you feel all those things is so obvious it’s almost invisible. There are cars everywhere. And I mean everywhere. Crammed along the curbs, congested on the street, taking up space everywhere.

There’s nothing wrong, technically, with this street. These scenes are everywhere. But the reason you feel all those things is so obvious it’s almost invisible. There are cars everywhere. And I mean everywhere. Crammed along the curbs, congested on the street, taking up space everywhere.

I know you know this. Like me, you’ve read all the statistics about the increasing number of cars on our streets. But maybe you were like me and didn’t really stop to think about what that means to your everyday bicycle commute.

What opened my eyes was a comment from a reader named Stu on my piece a couple of weeks ago about vehicular cycling. Here is part of Stu’s comment.

I can barely remember 1976, but what I do remember is that I could bike down most streets and not encounter a motor vehicle. Today it is the (opposite), no matter how ‘residential’ the street, the chance of not meeting up with a MV is slim. Times have changed, everyone seems to own a car or two and they use them for even the shortest of trips.

Something about Stu’s comment stuck in my head. I started imagining my bicycle commute in 1976. I’d be riding a steel-framed 10-speed in tiny shorts and knee socks, my feathered hair unencumbered by a helmet, and I would pass down a residential street with no cars. It’s almost unimaginable (not the hair, the image of a street with no cars).

So I did some digging into the impacts of increasing car ownership rates on the physical space in a city. Beware incoming numbers:

I live in Calgary, Canada. Back in 2008, the number of registered motor vehicles in the city was 829,030, according to this. By 2015, that number had grown to 1,005,109, according to this. That’s an increase of 176,079 vehicles in about seven years.

Think about how much space that takes up in a city. If each vehicle is, say, five metres by two metres (that’s an estimate, mostly to make the math easier, but it’s in the ballpark), that’s 10 square metres we’ve lost for each of those vehicles. I know they aren’t all on the road at the same time, but no matter how you slice it, occupying 10 square metres more than 175,000 times is a lot of space — 1.76 square kilometres, to be exact.

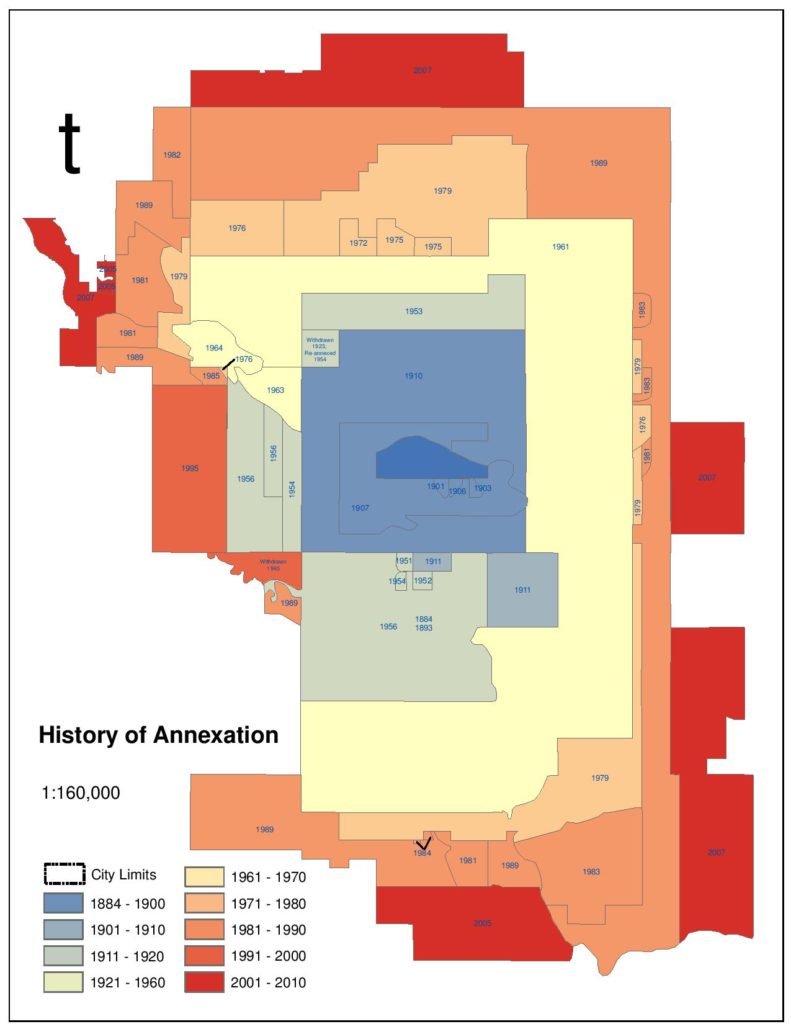

There’s more. According to the 2011 census, the size of Calgary is 704.51 square kilometres. For the sake of argument, let’s say that number didn’t change much between 2008 and 2015 (the city has grown, but not by much: Calgary’s wise but belated push to reduce sprawl, like basically every other city in North America, means there hasn’t been a big annexation since 2011, and the last major one was in the early 2000s).

A map of a land annexations in Calgary over the years.

That means the number of cars per square kilometre had grown to 1,426 in 2015, from 1,176 in 2008.

Think about the square kilometre around your house, and then imagine cramming in an average of 250 more cars in that space. Guess what? That happened over the last seven years, and you probably didn’t realize it.

Here’s one more thing to think about. I couldn’t find car ownership rates going back to 1976 to test Stu’s memory. But I did find this fascinating study from NYU, which compared vehicle ownership rates around the world between 1960 and 2002. In Canada in 1960, the number of vehicles per 1,000 people was 292. By 2002, that had climbed to 581. Based on a 2015 population of 1,230,915, the number of vehicles per 1,000 people in Calgary in 2015 was a whopping 816.

That isn’t an entirely apples-to-apples comparison, so I wouldn’t base your Ph.D thesis on it, but it does give you an idea of how many more motor vehicles are on the roads these days, and it’s a safe bet a similar story is playing out in other North American cities.

It also helps explain why you sometimes feel like an alien, unwelcome and pushed around, on your own street, when you ride a bicycle.

A well-functioning society of course needs motor vehicles, but Stu, it seems was right — our streets are much different now than they were just a few years ago, never mind back in 1976.

Much of this has happened unconsciously, so maybe a first step in making our cities more friendly is to start thinking about what enabled all those cars, and to take the steps necessary to curb the growth of car-ownership. We all, after all, have to share that space.

Follow Shifter on Facebook or Twitter. Follow Tom Babin on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.